What’s up, #VueFriends? It’s time for another Vue article. Today we will put into practice some vue design patterns dispersed on the Internet, but in this case, we pick some of the most useful to apply together with our beloved and great framework. Let’s go!

Table of contents

Why do we need design patterns?

A design pattern is a general, reusable solution to a commonly occurring problem within a given context in software design. That’s the purpose of design patterns, maybe you may find the solution to a given problem on your own, but today I want to show you some easier ways in Vue 😎.

Builder Pattern

If exists something cannot be missing in a web app, it is the forms, forms everywhere! Forms are boring and more if there is no way to generate them programmatically. It’s a common mistake to write files/components like UserForm.vue, ContactForm.vue, LoginForm.vue, and others with a similar logic inside.

That’s OK if your application has few forms, but what happens if your application has more than 20 or 100 forms? 😵. With some time, even naming them tends to get harder and harder. Think about the above scenario. How times do you write the <input> element, validations, styles, and bindings? So, don’t pray more 😀 here is the Builder Pattern!

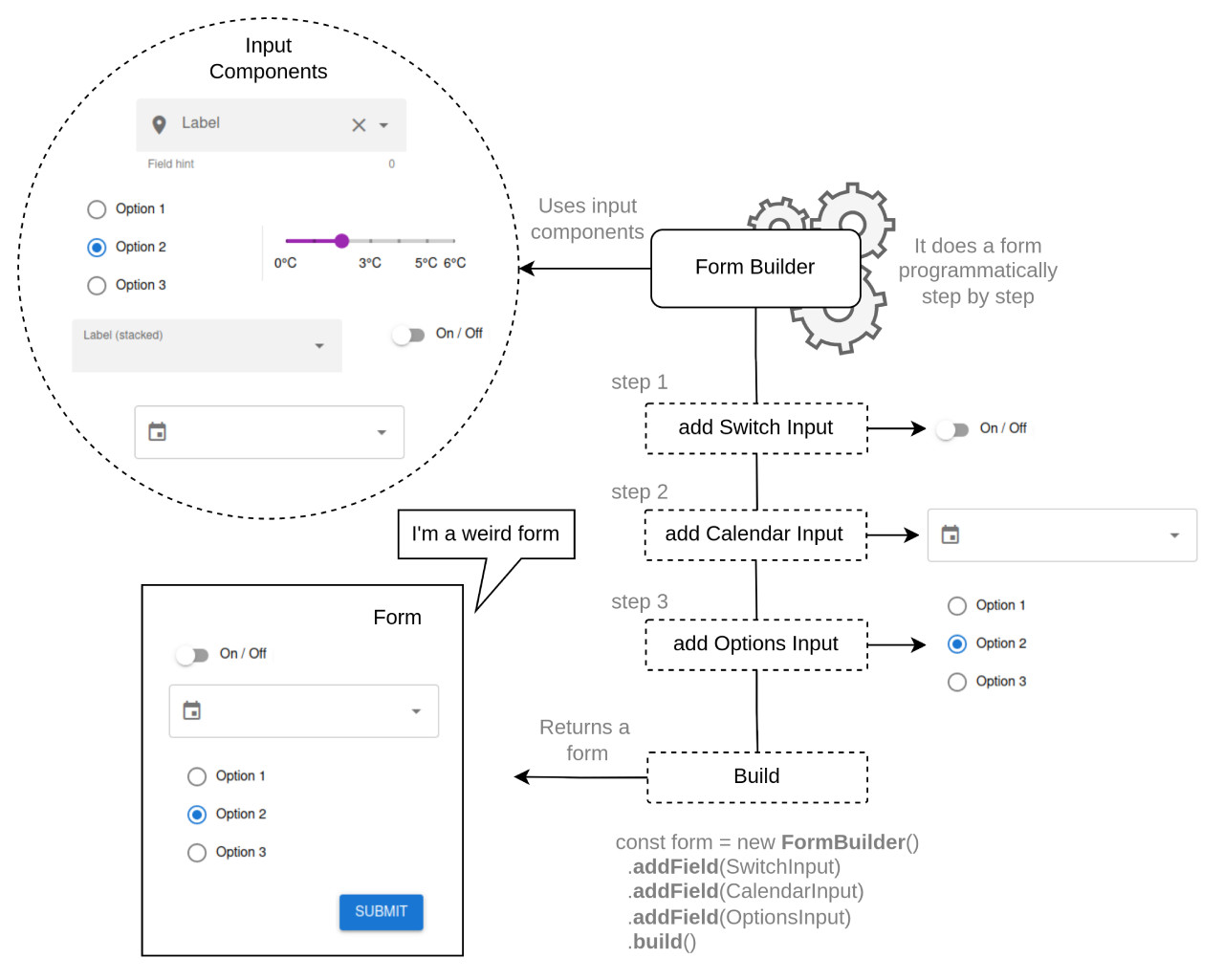

Builder is a creational design pattern that allows you to build complex object step by step. These patterns produce different types and representations of an object using the same construction code. Think about our case: we need to construct a form builder. Forms have many fields and submit button (maybe a cancel button too). One field means one kind of input, label, and error message. All fields have this structure and have an order.

First, we need to create the FormBuilder object as follows.

1 | import { defineComponent, h, type VNode } from "vue"; |

We need some structure to put all the fields in order. An array is enough (we are using Typescript, this approach adds more code). The method addField, as its name says, only has the task of putting an object Field to the fields array. The magic happens in the build method. It defines a new Vue instance with all our fields well structured.

Up to here, what we want is similar to the following schematic image.

Let’s continue, What is the FormFactory task? It’s responsible for structuring the form (many kinds of forms). Here is the code:

1 | <template> |

Maybe it isn’t the ideal Form Builder, but it’s useful. The more complex your form type, the more complex your form builder will be. Now you have a Form Builder, which you can use to create forms in each view, but we have one step more, the FormDirector. It has the task of structuring our forms in a single file with verbose methods, like makeLoginForm(), makeSignUpForm(), makeShopForm(), and more. Here is our FormDirector.ts.

1 | import VInput from "@/components/form/VInput.vue"; |

To validate our forms, we are using the zod library. As we can see, makeLoginForm() uses the Form Builder class to create a new app form with a detailed description of each field.

Code: vue design pattern repository, execute, and go to /builder-pattern route 😎.

Adapter Pattern

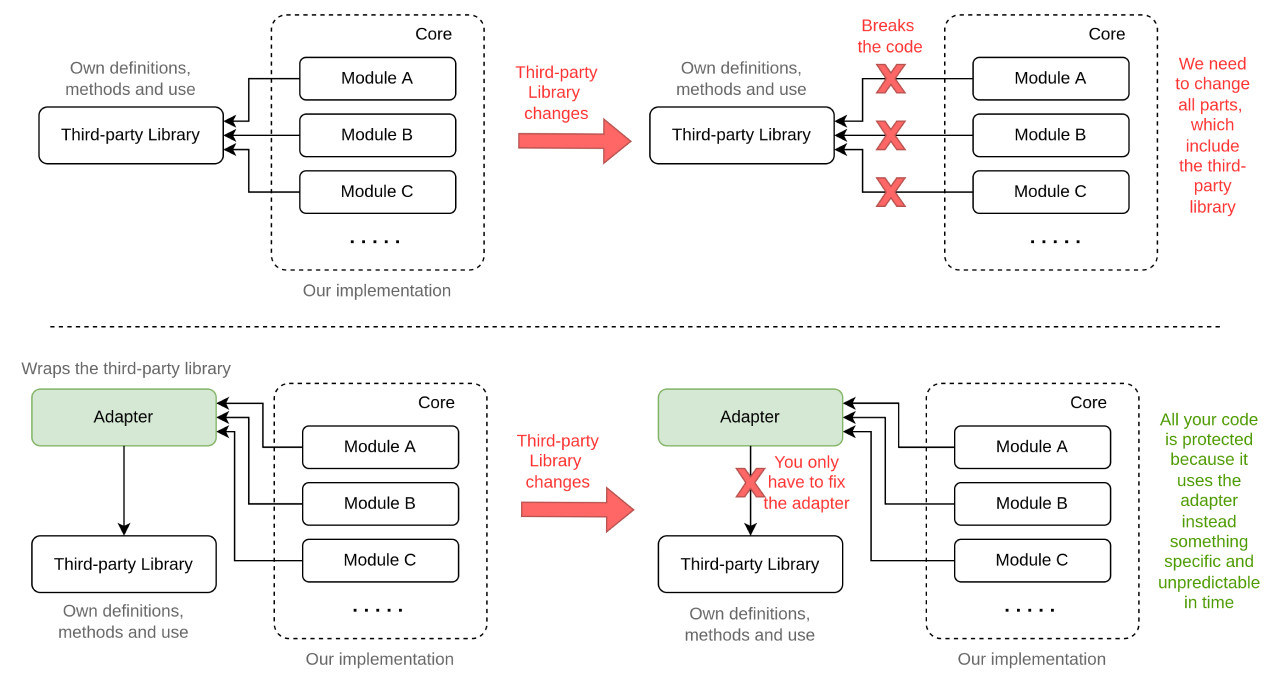

The adapter pattern is a structural design pattern also known as “Wrapper”. This pattern allows the interfacing of an existing class used as another interface, like something in the middle of a connection. The perfect real-world example is when you go to another country, you realize that the power plug is different. So, you will need an adapter to get power. That’s the magic.

A typical use case is to wrap a 3rd party library, which is used everywhere in your code. Someday, many libraries will be deprecated, or in the worst case, security issues, also known as vulnerabilities. To learn more about it, we have an amazing academy, https://websecurity-academy.com/, and a free guide related to Vue Security Best Practices.

In this case, we are using the js-cookie library to interact directly with our Cookies, which is simple and lightweight. The adapter looks like this.

1 | import Cookies from "js-cookie"; |

If one day we will need to replace the 3rd party library or add more features, it will be fast, and many parts of your code won’t be affected by this change, as we can see in the following schematic image.

Let’s think about another situation: You have an extensive web application with dozens of elements from some UI material library/framework (like Vuetify). Tomorrow, the business requirements change to adopt Quasar because of the long-term support. You have picked some elements from Vuetify, and now it’s time to change it 😨. But this scenario happens and could be acceptable, but as time goes on, technologies improve, and again a change is needed. What tedious work. The solution? Create your adapter input😎.

Container/Presentational Pattern

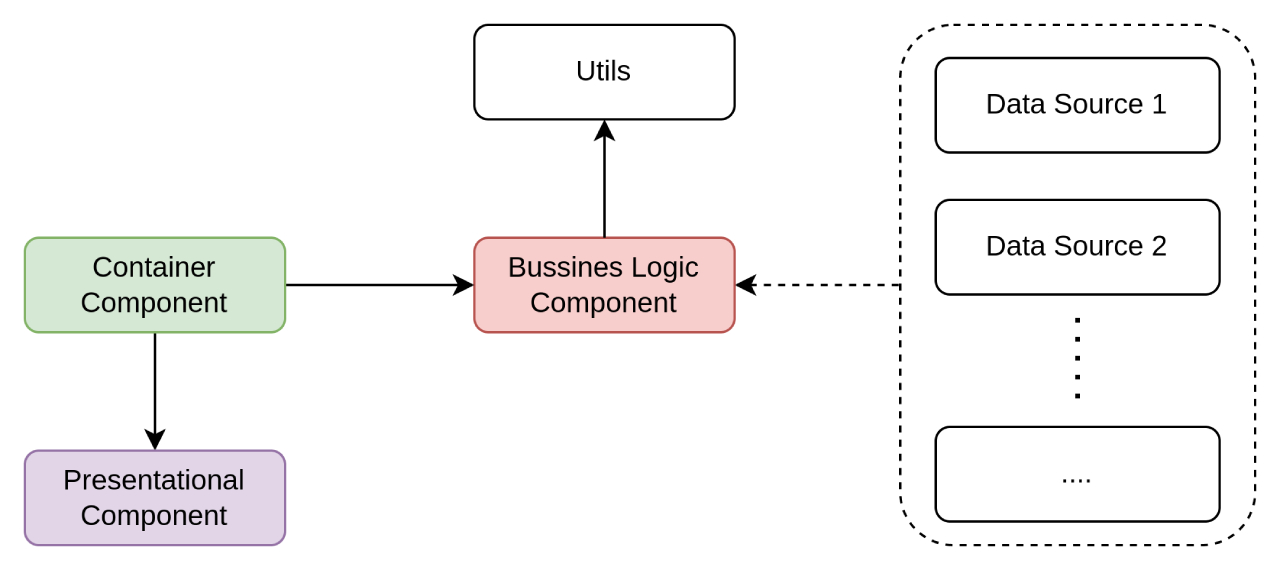

Maybe you are using this design pattern right now, it’s simple, and that’s the point. Vue and other modern frameworks have two parts where you can put the code, the presentational layer and the business logic layer. Those are known as concerns, and generally isn’t convenient to mix them up, but it doesn’t mean that one can’t use the other, and this is where Container or Presentational Pattern lands.

It’s time to imagine another scenario: You need a list of To-Do items. The easy way is to create a Vue SFC (Single File Component) to show all of them, something like this.

1 | <template> |

It works well, but what happens if we need to test this component all in one file the business logic layer (call to an API) is mixed with the presentational layer, so there is no way to reuse something and extract to test, sooner than later this type of code will need a refactoring. So, the Container Pattern helps us to decouple the presentational and business logic layer and turns to a testable application.

To take this pattern advantage, think of this file as three parts:

- Presentational Component, this component only has the task of receiving data through props, event bus, injection, state management system, or another to present this data visually.

- Business Logic Component/file has the task of fetching the data from somewhere (APIs commonly) to share with any component or file which needs it. It acts like an action administrator of all the actions registered on the presentational component.

- Container Component handles the interaction of the presentational component and the business logic component. In our case, this component calls some method to get the To-Dos’ information and will pass that data on to the presentational component as props.

So, it’s time to implement the code, first the Business Logic Component:

1 | import type { StoreOptions } from "vuex"; |

The todo.ts is a Vuex store definition with an API call inside. Disponible to any component which needs the list of to-dos.

The Presentational Component called VList.vue looks like this.

1 | <template> |

No matter the source, the data enters through props to display a list of beautiful To-Dos ✨.

Finally, the Container Component has the principal mission of calling the data from the Business Logic Component and passing the to-do data to display to the Presentational Component. Here is the code.

1 | <template> |

Code: vue design pattern repository, execute, and go to /container-pattern route 😎.

Provide/Inject Pattern

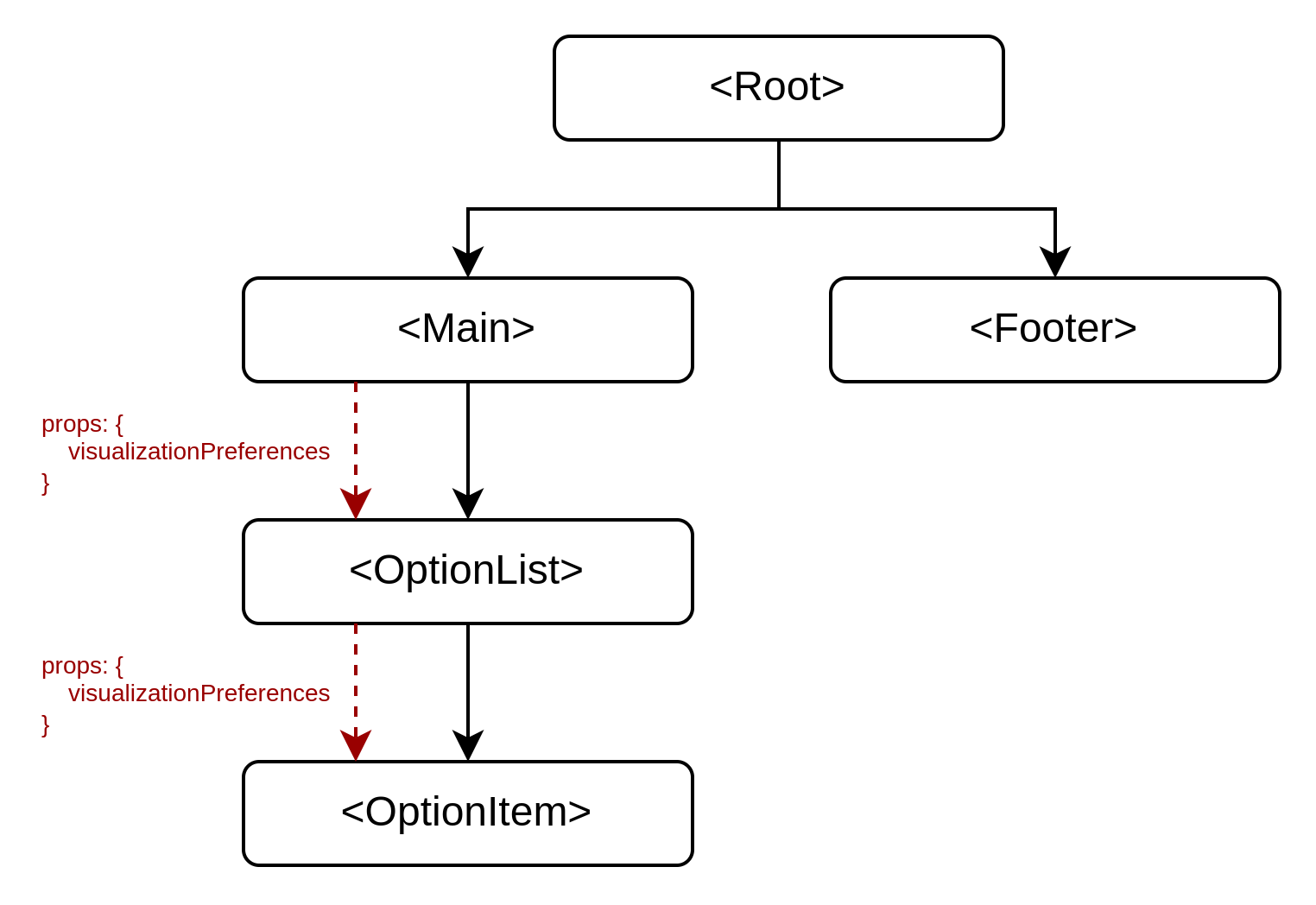

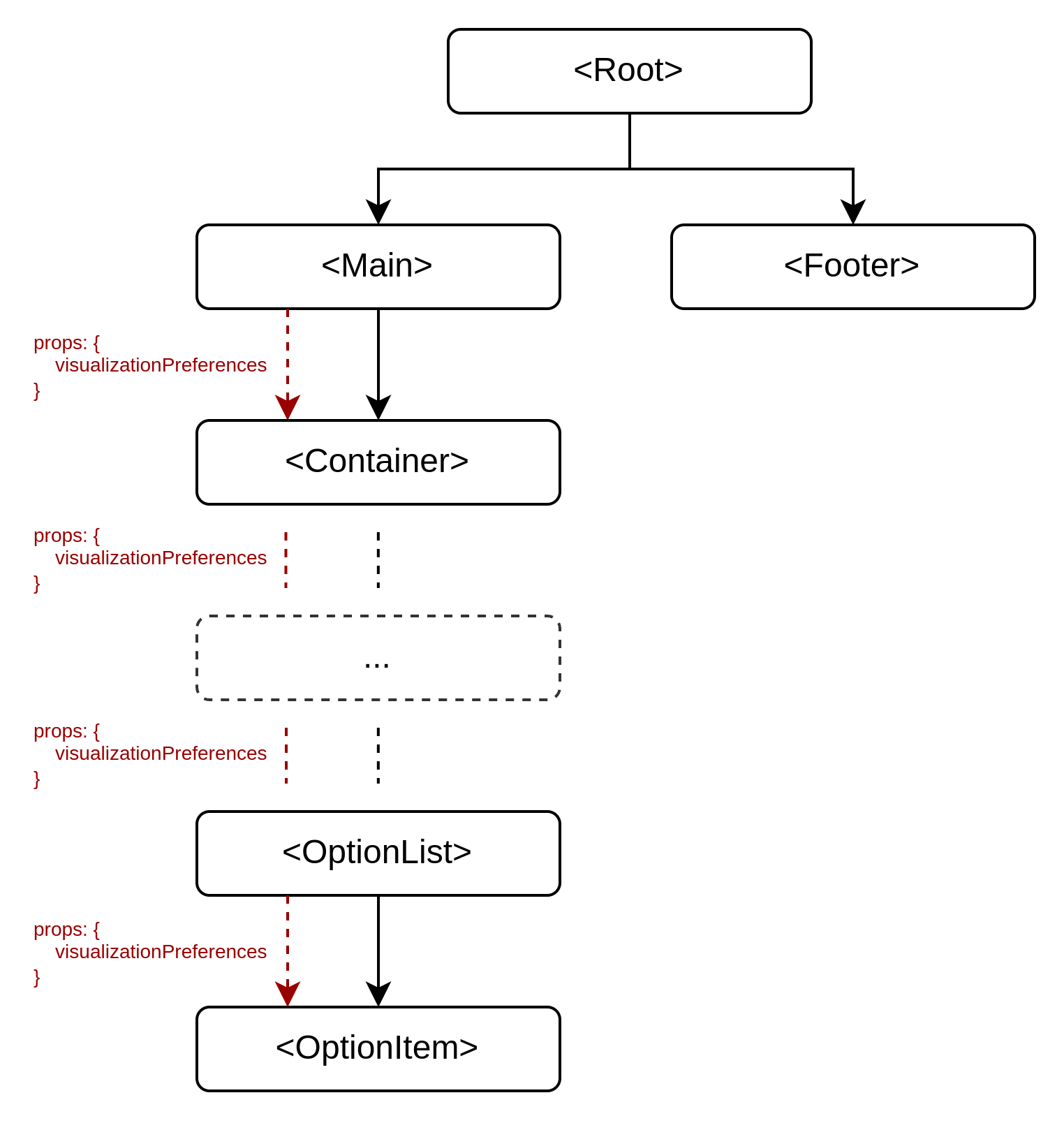

There is another interesting design pattern. When we start with Vue, most of us make the mistake of passing information through props between multiple components, as the image shows.

Ideally, the OptionList component should only render OptionItem, but with this approach, it contains visualizationPreferences as one of its props. It can still work without much trouble, but what if you must go through many components to get to the component that will use that property? Many of those components don’t need a new prop, only to fit with one component at the bottom of the hierarchy (a child component).

That problem is known as props drilling (an anti-pattern). Fortunately, Vue has the solution build-in with its provide() and inject() features, better known as dependency injection.

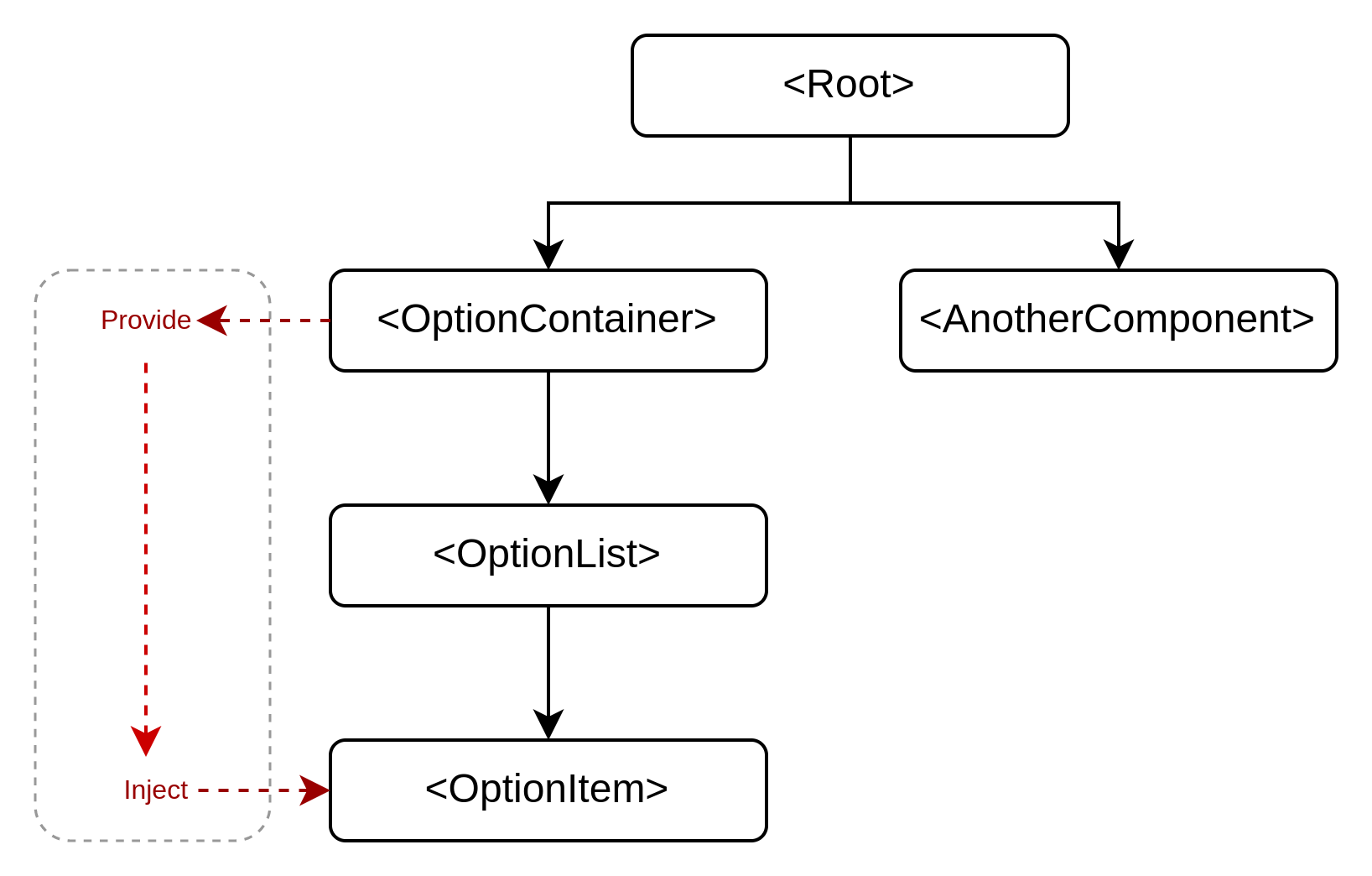

As we can see in the image above, Provide gets the data and is responsible for passing it when it is needed to be Injected in all the components down the hierarchy (in this case OptionItem).

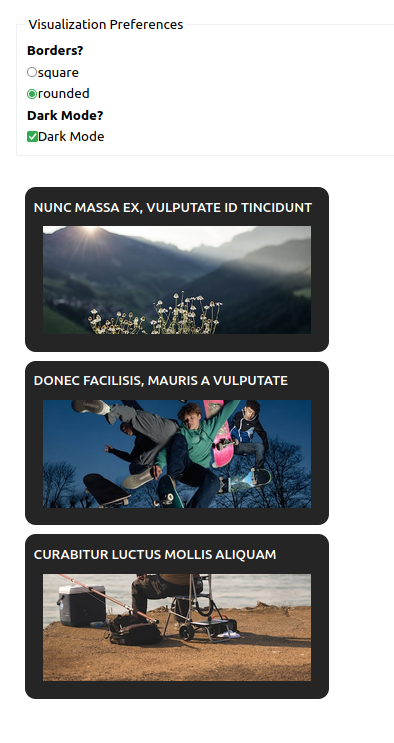

The following case shows a list of cards (with a title and image inside). We need to change the card appearance using provide() and inject(). Those cards have four styles: rounded, squared borders, and dark and light themes. This pattern is ideal for implementing more cards along the same behavior.

So, to implement this feature, we need to create the image structure in the code, beginning with OptionItem.vue.

1 | <template> |

OptionItem.vue pretends to be a card with a title and a random image inside.

The setup() uses the inject() method to retrieve (inject) the data from the provider() method, to be used in OptionContainer.vue (two components above in the hierarchy).

To inject that data inside the component, we need a key. In this case, VISUALIZATION_PREFERENCES is an InjectionKey. Its use makes sense with Typescript. It allows you to define a key name and structure for a specific data structure. The VISUALIZATION_PREFERENCES is in the OptionSymbols.ts file for re-usability purposes.

1 | import type { InjectionKey } from "vue"; |

The next component implemented is OptionList.vue, which works as a Presentational Component (only renders every OptionItem component if it has the necessary data, it is only a dummy component).

1 | <template> |

Now, the OptionContainer.vue is the Provider. It contains the data to pass to OptionItem.vue through the provide() method, as we can see below.

1 | <script lang="ts"> |

The code is large (this is the script part only). The provide() method receives the same VISUALIZATION_PREFERENCES seen previously as the first parameter, and the data to be injected as a second parameter (we are using computed() to turn reactive that data).

Many people use this pattern without the reactive feature, but it is great to have.

Code: vue design pattern repository, execute, and go to /provide-inject-pattern route 😎.

Composables

If you are coming from React, this reactive pattern could be familiar. Yes, we are talking about hooks, but in Vue, they are called “Composables”; hooks and composables are component patterns. According to the official documentation of Vue, a “composable” is a function that leverages Vue’s Composition API to encapsulate and reuse stateful logic. Stateful logic involves a managing state that changes over time.

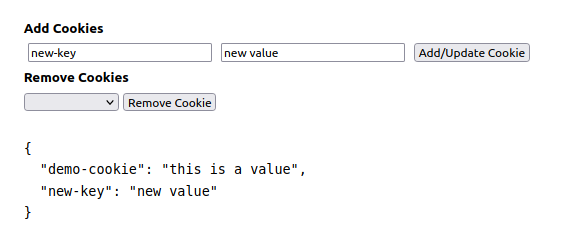

Let’s take advantage of the previous example explained in the Adapter Pattern. We have the class CookiesAdapter which wraps the js-cookie library. CookiesAdapter could be used directly in our code, but now we will add state and covert to a Composable, to see the cookies’ body reactively.

1 | import { ref, type Ref } from "vue"; |

The ref() method is a function that gives reactivity to a variable, cookies. In this case, when we talk about composables, we are directly talking about state and action exposure. This composable exposes three actions: get(), set(), and remove(); those do the same thing as the CookiesAdapter methods but are necessary to share through components as a composable, the same with cookies which is the general state of our Cookies. The trick behind the update() method synchronizes the cookies’ state every time an action is called.

Now, we can use it everywhere.

1 | <template> |

Many people use this pattern without the reactive feature, but it is great to have.

This cookie composable is cool, but if you don’t want to reinvent the wheel, the Vue ecosystem has many composition functions on the hand of VueUse and vue-composable libraries.

Code: vue design pattern repository, execute, and go to /composable-pattern route 😎.

State Management Pattern

State management is a crucial part of our web apps. In Vue, we have two great libraries to handle the state. To explain those libraries, we have the following case: We want to show to-do items in a list, to-do items retrieved from an open API (https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/todos). Similar to the case exposed in the Container Pattern section, we will reuse the VList.vue component. Now, we only need to think about how to use both state management libraries.

Vuex/Pinia

Accordingly, with the official documentation of Vuex, it serves as a centralized store for all component in an application, with rules ensuring the state, which can be mutated predictably. The following code shows a Vuex store configured to manage to-dos.

1 | import type { StoreOptions } from "vuex"; |

In contrast, we have the same implementation but powered by Pinia.

1 | import type { Todo } from "./../types/todo"; |

The unique difference is that Pinia doesn’t need to define mutations. We need a new component and use the to-do store implemented above with Vuex.

1 | <template> |

The Pinia version looks like this.

1 | <template> |

Both work well, but the superficial differences are few. But Pinia hides something really interesting. We are using Pinia as a Composable. Remember, the principal mission of this pattern is to manage and expose the state in a good way. Naturally, Pinia does that and fits in. but the Pinia approach has another advantage, Type friendly. We don’t need to point specific stores, actions, mutations, getters, or others via strings (a non-type friend); it happens in Vuex. In the past, that detail always caused me problems with the code. Instead, in Pinia, each state, action, or getter will be accessible directly from the source as a useStoreSomething(). Pinia is the new by-default state management library for Vue. We recommend using it belong the composition API.

Code: vue design pattern repository, execute, and go to /store-management-pattern route 😎.

Summary

Writing this article was a big challenge for me. I hope these examples and guideline helps you to make the best architectural decisions. Getting motivated and up to date is hard. If you found it useful, don’t doubt to share this article with your #VueFriends.

I don’t want to say goodbye without first recommending the Lachlan Miller’s book called “Design Pattern for Vue.js. A Test-driven Approach to maintainable Applications” which inspired me to write this article and the magnificent conference of Jacob Schatz (you will find more advanced patterns with Vue).

As we mentioned earlier, all the code is available here. Clone, execute, and enjoy it. Says goodbye, your #VueFriend @cr0wg4n.

Comments