Introduction to Content Security Policy

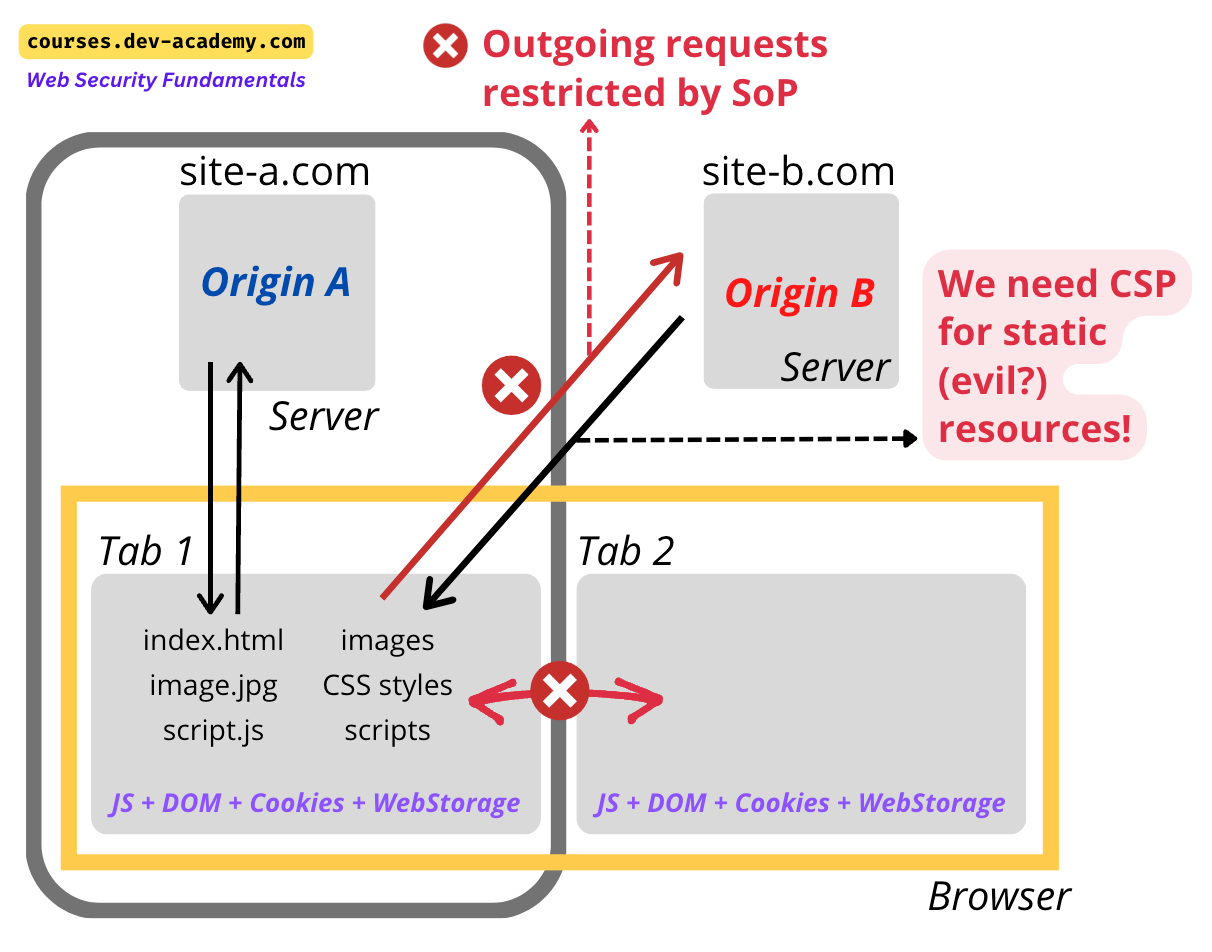

The security of modern web applications primarily relies on the Same-Origin Policy (SOP), which restricts how documents or scripts from one origin can interact with resources from another origin. This fundamental security feature helps to mitigate certain security risks by preventing unauthorized cross-origin access to resources and data. However, as web applications become more complex and rely on various third-party resources, the limitations of SOP in preventing modern threats, such as cross-site scripting (XSS), become apparent. While SOP prevents some cross-origin interactions, it does not directly address the issue of malicious scripts being injected and executed within the same origin.

To enhance security and address these modern threats, Content Security Policy (CSP) has emerged as a complementary mechanism. CSP provides an additional layer of security by allowing developers to specify precisely which resources are permitted to load and execute on their web pages, thus significantly enhancing the overall security posture of web applications. Below diagram, from Web Security Fundamentals - Starter Kit, presents the idea of SoP and CSP visually.

Table of Contents

Definition and Purpose of Content Security Policy

- Content Security Policy (CSP) is a security mechanism designed to add an extra layer of security for web applications.

- The policy allows developers to restrict which resources (such as JavaScript, CSS, images, and others) can be executed in the context of the website.

- Solid implementation of the CSP reduces the risk of cross-site scripting (XSS), clickjacking, and other code injection attacks.

- Adding a Content Security Policy is not exempt from other important security measures like input validation, filtering, and sanitization but a means of following a defense-in-depth approach providing an additional layer of security if the previous ones fail.

How Content Security Policy Works

Mitigating Cross-Site Scripting and Injection Attacks

CSP allows developers to reduce or eliminate the ability to trigger malicious scripts by specifying which sources of executable scripts (including inline scripts) should be considered legitimate by the browser. Inline scripts can be restricted through CSP to prevent script injections, using hashes and nonces to allow specific inline scripts to run while maintaining security.

In a “dynamic“ web application that consumes API data and/or accepts user input, one or more scenarios usually happen:

- Data is fetched from the server or API.

- Data is presented to the user.

- Data is transformed according to the business logic.

- Data is sent to the server or API.

When the website is exploited with XSS, a malicious script can manipulate each of these steps. This can happen when unsolicited content is injected and executed on the client’s browser (for example, in a search feature, a query string is injected into the DOM, but that string contains an executable JavaScript that performs an attack). Phishing, data theft, session hijacking, and unauthorized actions are just a few examples of what an attacker can achieve.

Formjacking and Skimming Attacks

One special case of XSS attacks is well known in the e-commerce industry. When the payment page containing form inputs for the user’s credit card data is exploited with XSS, that data can be sent to the place pointed by a malicious script, effectively stealing it.

Preventing Clickjacking Attacks

Another attack vector that CSP implementation can mitigate is when the attacked website’s content is embedded in an invisible iframe on the malicious website. Here is how it works:

- A user visits an (evil) website that has an encouraging click button (like “You won $100“).

- That (evil) website has attacked the website embedded in an invisible

<iframe/>. - The unsuspecting user clicks the button on the attacked website.

- The action is executed on behalf of that (potentially logged-in) user.

The embedded website may be positioned absolutely so that when the user clicks on the proper place on that evil website, the real click happens on the embedded one (not the visible one), potentially executing some sensitive operation. It may be anything, from liking a post, sending a message, or even sending money in a one-click checkout.

Enforcing HTTPS and Preventing Mixed Content

CSP can specify the allowed protocols, such as HTTPS, to ensure that browsers load content securely. Mixed content occurs when initial HTML is loaded over a secure HTTPS connection, but other resources (such as images, videos, stylesheets, scripts) are loaded over an insecure HTTP connection. This can create vulnerabilities, as the non-secure resources can be intercepted or manipulated by attackers. CSP can prevent mixed content by blocking requests to non-secure HTTP URLs, thereby ensuring that all resources are loaded securely.

Example Policy Implementation

Let’s examine a sample CSP implementation, that https://spotify.com returns as of today. The policy contains two directives.

1 | script-src 'self' 'unsafe-eval' blob: open.spotifycdn.com open-review.spotifycdn.com quicksilver.scdn.co www.google-analytics.com www.googletagmanager.com static.ads-twitter.com analytics.twitter.com s.pinimg.com sc-static.net https://www.google.com/recaptcha/ cdn.ravenjs.com connect.facebook.net www.gstatic.com sb.scorecardresearch.com pixel-static.spotify.com cdn.cookielaw.org geolocation.onetrust.com www.googleoptimize.com www.fastly-insights.com static.hotjar.com script.hotjar.com https://www.googleadservices.com/pagead/conversion_async.js https://www.googleadservices.com/pagead/conversion/ https://analytics.tiktok.com/i18n/pixel/sdk.js https://analytics.tiktok.com/i18n/pixel/identify.js https://analytics.tiktok.com/i18n/pixel/config.js https://www.redditstatic.com/ads/pixel.js https://t.contentsquare.net/uxa/22f14577e19f3.js 'sha256-WfsTi7oVogdF9vq5d14s2birjvCglqWF842fyHhzoNw=' 'sha256-KRzjHxCdT8icNaDOqPBdY0AlKiIh5F8r4bnbe1PQwss=' 'sha256-Z5wh7XXSBR1+mTxLSPFhywCZJt77+uP1GikAgPIsu2s='; frame-ancestors 'self'; |

Starting with the first directive script-src, we can see it allows the execution of:

- Scripts downloaded from

https://spotify.comas defined by'self'. - JavaScript’s

eval()and similar methods likenew Function()as defined by'unsafe-eval'(let’s hope Spotify engineers know what they are doing). - Binary files as defined by the

blob:scheme (maybe for streaming music?). - Scripts downloaded from the listed domains (

open.spotifycdn.com,open-review.spotifycdn.com,quicksilver.scdn.co,www.google-analytics.com, just to point out the first ones). - Exact script files downloaded from the URLs listed (for example,

https://www.googleadservices.com/pagead/conversion_async.jsorhttps://www.redditstatic.com/ads/pixel.js). - Scripts where the hash digest calculated by SHA-256 is exactly equal to one of the listed sources (for example,

'sha256-WfsTi7oVogdF9vq5d14s2birjvCglqWF842fyHhzoNw=').

The second directive frame-ancestors with the value 'self' allows embedding spotify.com content only on pages loaded from its own origin (look above at clickjacking).

Understanding CSP Directives

Fetch Directives

The following directives define valid sources of content (including 'self' that represents the current page’s origin):

script-src- Scripts that can be executed.style-src- Stylesheets or CSS.img-src- Images.font-src- Web fonts.media-src- Audio and video.object-src-<object>,<embed>, and<applet>elements.child-src- Web workers and nested contexts like<frame>and<iframe>.connect-src-Fetch,XHR,WebSocket, andEventSourceconnections.manifest-src- Application manifests.worker-src-Worker,SharedWorker, orServiceWorkerscripts.

The directive default-src serves as a fallback for the other fetch directives. If none of the fetch directives apply to a particular resource type, the default-src directive is used.

Document Directives

The directives listed below control the capabilities of the document:

base-uridefines a set of allowed URLs for the HTMLbasetag (to prevent attackers from altering the base URL to manipulate how relative URLs are resolved).form-actiondefines valid sources (URLs) which can be used as the target of a form submissions.frame-srcdefines valid sources for nested browsing contexts loading using<frame>and<iframe>(whilechild-srcwas initially introduced to replaceframe-src,frame-srchas been reintroduced in CSP Level 3 to provide more granular control).sandboxapplies restrictions to a page’s capabilities (details below).plugin-typesrestricts the set of plugins that can be embedded into the document.

The sandbox directive

This directive applies a set of restrictions to a page’s capabilities, providing an additional layer of security by limiting what a page can do. When this directive is used, it enables a sandboxing mode for the document, which can help mitigate risks from potentially malicious content. The restrictions can include disabling scripts, preventing the document from submitting forms, blocking plugins, and more. The directive can take several tokens to specify the desired restrictions, such as:

allow-forms: Allows the document to submit forms.allow-same-origin: Allows the document to maintain its origin, enabling it to access data and resources from the same origin.allow-scripts: Allows the document to execute scripts.allow-popups: Allows the document to open pop-up windows.allow-modals: Allows the document to open modal windows.allow-orientation-lock: Allows the document to lock the screen orientation.allow-pointer-lock: Allows the document to use the Pointer Lock API.allow-presentation: Allows the document to start a presentation session.allow-top-navigation: Allows the document to navigate the top-level browsing context.

By default, without any tokens, the sandbox directive applies all possible restrictions, effectively isolating the document from most capabilities.

The plugin-type directive

This directive restricts the set of plugins that can be embedded into the document, enhancing security by controlling which types of content are allowed to be embedded. This directive specifies the MIME types of plugins that the document can load, preventing the execution of potentially harmful plugins. For instance, if a site only requires a specific type of plugin, this directive can be used to block all other types, reducing the attack surface. Example usage: plugin-types application/pdf: Only allow the embedding of PDF files.

frame-ancestorsdefines valid places where the page can be embedded in a frame (`self’ means only the same origin can frame the content).navigate-torestricts the URLs that the document may navigate to.

Reporting Directives

As web applications grow more complex, monitoring and addressing security policy violations become crucial. Built-in in CSP reporting mechanisms specify how and where violation reports should be sent. This issue is further detailed in the Error Messages and Reporting paragraph. Now, let’s list the directives that control the reporting functionalities:

report-uri[deprecated] specifies the URI to which the user agents send reports about policy violations.report-tospecifies the reporting group to which the user agent sends reports about policy violations.

In recent updates to the Content Security Policy (CSP) specifications, starting from CSP Level 3, the report-uri directive has been deprecated in favor of the more robust report-to directive. The report-uri directive was used in earlier CSP versions to specify the single endpoint where the browser should send reports of CSP violations. It is being phased out because it lacks the flexibility and capabilities needed for modern web security practices.

The report-to directive, introduced in CSP Level 3, allows for defining multiple reporting endpoints and supports detailed configuration through the Reporting API. This enables more granular control over the collection and handling of violation reports. The shift from report-uri to report-to enhances the ability of developers to monitor and respond to security threats more effectively.

Other Important Directives

script-src-elemspecifies valid sources for JavaScript<script>elements.script-src-attrspecifies valid sources for JavaScript inline event handlers.style-src-elemspecifies valid sources for<style>elements and<link>elements.style-src-attrspecifies valid sources for inline styles.

Note that the script-src directive specifies valid sources for all JavaScript execution contexts, including external script files, inline scripts, and event handler attributes.

Understanding Source Types in CSP

Content Security Policy allows developers to specify various source types to control which resources can be loaded and executed on their web pages. These source types include domains, paths, and special keywords such as 'none', 'self', 'unsafe-inline, and 'unsafe-eval'. Understanding and appropriately using these source types is fundamental to creating a robust CSP.

Domains:

Example:script-src https://trusted.cdn.com

Domains specify trusted external sources from which resources can be loaded - listing specific domains ensures that only content from these sources is allowed.Subdomains:

Example:img-src *.example.com

Wildcards can be used to specify subdomains, allowing resources from any subdomain of a given domain. This permits flexibility while maintaining control over trusted sources.Full URLs:

Example:script-src https://example.com/scripts/main.js

Full URLs allow only exact matches, providing the highest level of specificity. This ensures that only particular resources are loaded from trusted locations.Protocols:

Example:media-src https:

Protocols such as https: allow resources from any domain using the specified protocol, ensuring secure connections.Data URIs:

Example:img-src data:

Data URIs permit embedding small files directly in HTML or CSS. This is useful for including inline images or fonts but should be used cautiously due to potential security risks.Special Keywords:

- ‘none’: Blocks all resources of the specified type. For example,

script-src 'none'ensures that no scripts are executed, providing maximum security. - ‘self’: Allows resources to be loaded only from the same origin. For instance,

img-src 'self'ensures images are loaded only from the same origin. - ‘unsafe-inline’: Permits the execution of inline resources, such as scripts and styles. This reduces security by making the site vulnerable to XSS attacks and should be avoided.

- ‘unsafe-eval’: Allows the use of JavaScript’s

eval()function and similar methods. This poses a high-security risk and should only be used when absolutely necessary.

- ‘none’: Blocks all resources of the specified type. For example,

By understanding and utilizing these various source types, developers can create detailed CSP rules that balance security and functionality, ensuring that only trusted sources are permitted to load and execute content. This granular control is essential for protecting web applications from a broad range of threats.

Content Security Policy Header

Understanding the Content Security Policy Header

The Content-Security-Policy header is an HTTP response header that a web server sends back to instruct the browser about the provided restrictions. It is used to define multiple directives that specify which sources of content are allowed to be executed within a website.

CSP Policy Types

Within the industry, we can distinguish two distinct categories of Content Security Policy implementation.

Allowlist-based CSP

This type of CSP defines multiple content sources (like domains or paths) that can be executed within a web page. The Spotify example we analyzed before is this kind of Allowlist-based CSP.

Strict CSP

According to researchers at Google, “strict” CSP is nonce-based and/or hash-based only. It does not favor using a list of origins or domains as allowed sources of content. The idea behind advocating this approach is that the allowed list may grow large and be hard to maintain for complex web applications. Another reason is the empirical discovery that allowed origins often expose vulnerable endpoints allowing the injection of malicious content. Here is the referenced study.

Nonce-based CSP uses unique one-time-use random values for each HTTP request. Each script that is allowed to run in the browser is marked with a nonce attribute containing the value matching the nonce from the HTTP header. This requires dynamic templating provided by the Web application synchronizing the rendered HTML with HTTP headers.

Hashes-based CSP uses hashes (for example SHA-256) to allow specific scripts to be executed. Each change in the script must be reflected in the matching hash inside the Content Security Policy HTTP header.

Finally 'strict-dynamic' CSP directive tells the browser to trust child scripts created by trusted scripts with the correct hash or nonce.

That approach may not be possible for web applications without the possibility to synchronize HTTP header values with HTML templates containing script tags with nonces and hashes. Also, in (a very common!) case of using Content Delivery Networks (CDNs), this approach is impractical, because CDNs typically cache static content to enhance performance. If the main script requires a unique nonce for each request, this dynamic nature conflicts with the static caching mechanism of CDNs.

Implementing Content Security Policy

Server-Side Configuration

Implementing CSP typically begins with server-side configuration. This involves instructing the server to respond with the HTTP response header Content-Security-Policy containing a list of directive and source pairs. For instance, a basic CSP header might look like this:

1 | Content-Security-Policy: default-src 'self'; script-src 'self' https://trusted-cdn.com; |

This configuration tells the browser to load all content from the same origin by default and to allow scripts only from the same origin and a trusted CDN. The server-side configuration ensures that the policy is consistently applied to all pages served by the server, making it a reliable method for enforcing CSP across an entire web application. It is important to carefully craft and test the policy to avoid blocking legitimate resources, which can disrupt the application’s functionality.

Client-Side Implementation (Meta Tag)

In scenarios where server-side configuration is not feasible, the Content-Security-Policy <meta> tag can be used to deliver a CSP. This approach is useful for static websites or environments where modifying server headers is not possible. The meta tag is placed within the <head> section of the HTML document:

1 | <meta http-equiv="Content-Security-Policy" content="default-src 'self'; script-src 'self' https://trusted-cdn.com"> |

While using the meta tag for CSP implementation can be convenient, it has limitations. The list of directives available for meta tags is more restricted compared to server-side headers. Additionally, meta tags are parsed after the initial HTML document is loaded, which can delay the enforcement of the policy and potentially allow some initial resource loads that would otherwise be blocked by a server-side CSP header. Despite these limitations, the meta tag method provides a flexible option for adding CSP to pages where server configuration changes are impractical.

Error Messages and Reporting

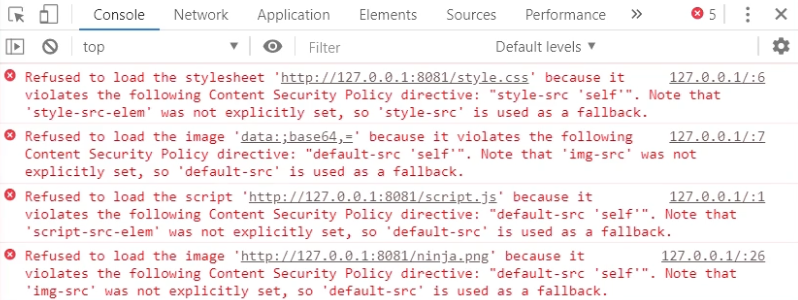

Understanding CSP Error Messages

When a policy violation occurs, error messages are displayed in the browser’s console, providing immediate feedback on which resources or actions are blocked by the Content Security Policy (CSP). These console messages are essential for developers to diagnose and troubleshoot issues related to CSP implementation. However, relying solely on console error messages can be limiting, as they do not provide a comprehensive view of how the policy affects real users in the field. To gain deeper insights and monitor CSP violations more effectively, CSP reporting features can be utilized.

Reporting Feature

To gain deeper insights and monitor CSP violations more effectively, CSP reporting features can be utilized. These features specify how and where violation reports should be delivered. When a CSP violation occurs, the browser logs the violation and sends a report to a designated endpoint, providing valuable insights into which resources or actions were blocked. Here is a sample CSP violation report sent to the reporting endpoint:

1 | { |

Report-Only Header

The Content-Security-Policy-Report-Only header allows developers to test and fine-tune their CSP without immediately enforcing it. By using the report-only approach, the browser logs any violations of the CSP directives and sends these reports to the specified endpoint. These reports provide valuable insights into which resources or actions would be blocked under the enforced policy, highlighting potential issues and areas for adjustment without breaking the working application features.

This proactive approach enables developers to monitor and understand how their proposed CSP impacts the website’s functionality and security before full enforcement. By analyzing these reports, developers can iteratively refine their CSP to balance security and functionality, ensuring that legitimate content is not inadvertently blocked and that the policy effectively counters malicious activities. Implementing a report-only CSP and leveraging detailed reports is a crucial phase in deploying a robust and functional CSP. It helps identify and mitigate risks, ultimately enhancing the security posture of web applications while maintaining a seamless user experience.

Best Practices for Implementing CSP

Start with a Report-Only Approach:

Begin by deploying CSP in report-only mode to identify potential issues without affecting the user experience. Monitor and analyze the violation reports to refine the policy.Iterative Policy Development:

Develop the CSP iteratively. Start with a basic policy and progressively add more directives, testing each step to ensure that legitimate resources are not blocked.Use Nonces and Hashes:

Try to avoid inline scripts and styles by exporting them to separate files hosted on the page’s origin. If an inline script is an absolute must, use a nonce or hash instead of allowing'unsafe-inline'. This enhances security by allowing specific inline code while blocking others.Regular Audits and Updates:

Regularly audit the CSP and update it to reflect changes in the web application, such as new resource dependencies or changes in third-party services.Comprehensive Testing:

Test the CSP across different browsers and devices to ensure consistent behavior. Utilize browser developer tools to debug and refine the policy.

By following these best practices and carefully implementing CSP using server-side headers or client-side meta tags, developers can significantly enhance the security of their web applications, protecting against a wide range of attacks while maintaining functionality and user experience.

Limitations and challenges

When to Use Content Security Policy

CSP provides the most value for “dynamic” web applications, where data is fetched from APIs with DOM manipulation and where users interact with the UI. On the other hand, for “static” websites where the content is purely presentational (just HTML + CSS, without any JavaScript code), implementing a Content Security Policy can disallow embedding it on other websites (with the frame-ancestors directive). If there is no functionality on the page (think: “static” website), there is very little that can be “hacked” there (apart from unsolicited iframe embedding).

Limitations of a Content Security Policy

Creating and managing a Content Security Policy (CSP) is time-consuming and complex. This process requires a deep understanding of the resources used by the web application, including scripts, stylesheets, images, and third-party content. Each requested resource must be meticulously inventoried and categorized to ensure that the CSP allows legitimate content while blocking potentially malicious content.

Inventorying, aggregating, and understanding what each resource is doing after it has been discovered complicates things even further. Developers need to track every resource’s origin, purpose, and potential security risks. This often involves:

Comprehensive Resource Analysis:

Every script, style, image, and other resource must be analyzed to determine its source and role within the application. This includes third-party resources, which may have their own dependencies and security considerations.Dynamic Content Challenges:

Modern web applications frequently load content dynamically through APIs, which can vary based on user interactions and data. Ensuring that all dynamically loaded content adheres to CSP rules adds another layer of complexity.Third-Party Integrations:

Many web applications rely on third-party services for analytics, advertising, and social media integration. Each of these services introduces additional domains that need to be whitelisted in the CSP, increasing the policy’s complexity and the potential attack surface.Maintenance Over Time:

As the application evolves, new resources are added, and existing resources are modified or removed. Maintaining an up-to-date CSP requires continuous monitoring and updating, which can be labor-intensive.

Conclusion

Summary of Content Security Policy

Content Security Policy (CSP) is a critical security standard that provides an additional layer of protection for web applications. By allowing developers to specify which resources can be loaded and executed, CSP significantly reduces the risk of XSS and other code injection attacks. This security mechanism helps safeguard sensitive data, maintain the integrity of web applications, and protect users from malicious activities.

Importance of CSP in Modern Web Security

In today’s digital landscape, where web applications are increasingly complex and interconnected, the importance of CSP cannot be overstated. Web applications that process API data, accept user inputs, and interact with various third-party services are particularly vulnerable to security threats. Implementing a robust CSP is an essential part of a comprehensive security strategy. It acts as a powerful defensive measure against unauthorized script execution and data manipulation, ensuring that even if other security layers fail, CSP can help mitigate potential damage.

By continuously monitoring, testing, and refining CSP, developers and server administrators can maintain a strong security posture, adapt to emerging threats, and provide a safer user experience. In combination with other security best practices, such as input validation, filtering, and sanitization, CSP plays a pivotal role in fortifying web applications against a wide range of attacks. Embracing CSP is not just a technical necessity but a proactive step towards building resilient and trustworthy web applications in an ever-evolving threat landscape.

Comments